search

date/time

| Yorkshire Times Weekend Edition |

Steve Whitaker

Features Writer

@stevewhitaker1.bsky.social

1:02 AM 12th April 2024

arts

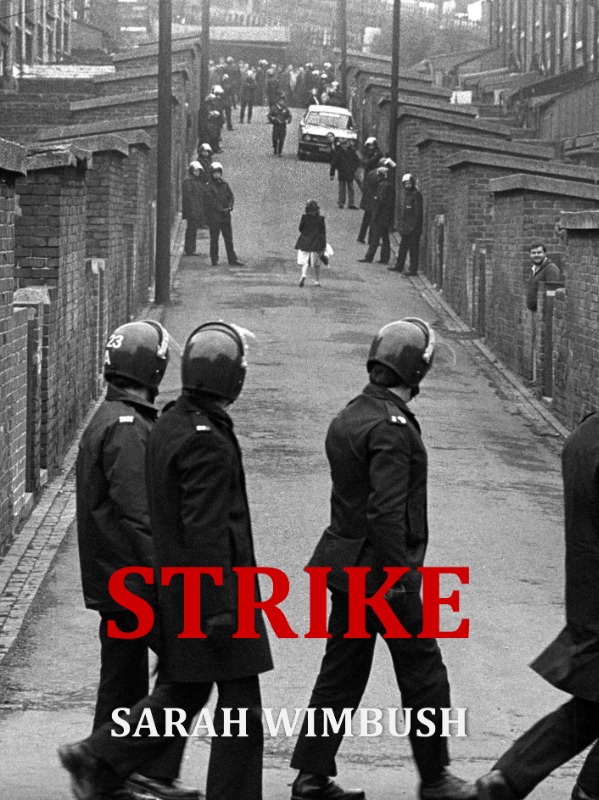

Blown Apart By The Sun: Strike By Sarah Wimbush

Charged with grievance, Strike’s earnest commemoration, in poems and pictures, of a time of cataclysmic change, is as persuasively distilled as a polemic. An inventory of words forged unbreakably, the opening prose poem of Wimbush’s fine collection gives a précis of what follows: ‘Our Language’ takes sides unequivocally, invoking every mechanism of mining culture, its accoutrements and vernacular, its stoicism and its anger, its women. The determiner ‘Our’ declares, as effectively as Tony Harrison in his ‘Family’ sonnets, a sense of belonging, to the class and people of the poet’s origins. On an unremitting journey of demotic terms, bearing defiance alongside ‘snap-tins’, and inferring pathos in all-consuming coal-dust, the language of a lost industry endures:

‘It’s Fuck the bastards. This

is the tune of haulage boys and shot-firers and Elvis

impersonators, their legs smashed to bits at the

bottom of shafts, and the women who feed everyone’s

children.’

And the women. As a mature student at the time of the Miners’ Strike in 1984, several of my fellow students were miners’ wives, women whose lives were both blighted by the conflict and paradoxically liberated by a higher education that might otherwise, owing to the hitherto rigidly patriarchal culture prevailing in pit districts, have been denied to them. One of Sarah Wimbush’s many concerns, here, is to celebrate the women who suddenly became visible during the strike – in food kitchens, in conversations with the press, sometimes on the picket lines with their husbands, fathers, brothers. Enfranchised by the circumstances in which they unexpectedly found themselves, these women are represented in Strike in poems and photographs, and it can be no wonder that some of the ‘firecrackers’ described in Wimbush’s fine poem of parity, ‘Queen Coal’, made it on to Politics and Social Science courses at university. The poem’s relentless rhythm and repetition hammers a drum of forbearance, selflessness and dogged loyalty:

‘What do they sing, these women, as their voice

jemmies the roof, with their Avon and home-perms,

widowhood and thrift - g’orn lads, g’orn lads!’

These are Chris Rea’s ‘Stainsby Girls’, or the women caught in the complex domestic traps of Barry Hines novels. From ‘Women’s Support Groups’ in the eponymous poem, who, tellingly, ‘…stand beside their husbands / instead of one step behind’, to those who rustled up basic snap on a shoestring of collection boxes and charity, these women share a social platform as partners in a struggle.

Each of Wimbush’s poems is a response to, and accompanied by, a contemporary photograph. The woman who ministers to, but takes no lip from, several seated miners in the Welfare Canteen at Houghton Main in John Smith’s suggestive image of 3rd August, 1984, is rendered an archetype in the poet’s words. Graven in stones of resistance, sanctified by effort, ‘Our Lady of the Pit Canteen’ is an equal of those men who ‘have jacked and packed pit props / on the roadways to hell’.

Poster: August 1984, Lesley Boulton at Orgreave. Image by John Harris

‘The stave, the stare.

The road, the air,

her bead necklace,

the horse’s breath,

her arm, raised,

his arm stretched’. (‘Mounted policeman canters towards Lesley Boulton’)

Sarah Wimbush’s philosophical positioning in a book that recalls the unfolding of a tragedy is capacious enough to acknowledge the presence of internecine division, contradiction and casualty, on both sides of an increasingly fractious divide. She is as summarily efficient in denouncing the BBC’s skewed coverage of the conflict – ‘Record. Rewind. Reverse’ – as she is quick to remember those – both picket and ‘scab’ – who needlessly died in the prosecution of their aims. The impromptu football match that took place between coppers and pickets at Bilsthorpe Colliery in March, 1984, in Denis Thorpe’s strikingly counter-intuitive image, is rendered ironic in hindsight by the poet’s words, which resound with the knowledge of what will follow, as surely as the short-lived Christmas Truce in the trenches:

‘Boys again, out on the Rec

kicking to win. While in the belly of England

the strike to end all strikes erupts.’ (‘Kick-off’)

Or the unlikely, life-saving kiss of police inspector to picket in Wimbush’s rather beautiful poem ‘The Kiss’, with which the tendering of the kiss-of-life of one US lineman to a dying other is deemed to share a greater correspondence than the stylized elegance of artistic representation. The point at which pictorial art fails is the point at which humility and compassion cast aside doubt in a single, profoundly human embrace, and in so doing, oblige us to reconsider the rules of engagement:

‘No, this is an older buss

from that darker, deeper place

a blue breath

offering the universe

inside a Morabito kiss.’

At her most incendiary when deconstructing the strike’s figureheads, Sarah Wimbush’s examination of motive and action is refreshingly free of cant. From this hardened perspective, there is no mitigation for Margaret Thatcher and little for an early strike-breaker. In adjacent poems – followed by a Gwent Food Fund poster and an image, by Peter Arkell, of a Nottinghamshire scab – and represented, respectively as a sapphire-eyed Caligula, and a ‘bankrolled doofus’ of Faustian instincts, Wimbush reserves her real savagery for the closing line of each, making of the former PM, a Lady Macbeth and of the blackleg, a ‘nobody’. And of Neil Kinnock, a near-nobody, blighted by indecision, ‘a man compressed / between left and left’. ‘When will you raise a hand to strike the hour?’, the narrator asks, not unreasonably (‘Kinnock’).

In an impressionistic triptych, Wimbush precedes the inner dynamism of a photograph, by Keith Pattison, of Arthur Scargill speaking at a rally, with words that celebrate the miners’ leader’s own fondness for the lexicon as they illustrate his, sometimes faulty, perspicacity:

‘There could be other words, other skies

But his eyes – blue and infinite – have limitations,

there’s one path lads: picket!’ (‘Scargill’)

Arthur Scargill speaking at the Barbary Coast Club, Sunderland, 1984. Image by Keith Pattison

But beyond the division is a sense of unity in a time of antagonism. Finding support in many quarters, Wimbush’s simple inventory of the ordinary and the quietly committed in ‘People who support the Miners’ reflects an attitude of robust, if wildly disparate, defiance:

‘People nailed to a laithe.

People who grow onions.

People from Borehamwood and Rottingdean.’

Perhaps because of its own cultural marginalization, the support of the lesbian and gay community - culminating in a benefit concert at the Electric Ballroom in Camden in December, 1984 – is a striking example of unexpected generosity. ‘Pits and Perverts’, opposite a poster for the gig, delivers a glorious poetic ‘dance’ in five celebratory quatrains, whose delicious rhymes and half-rhymes yield terpsichorean colour in a dark sedimentary terrain, and soften the hardest of hearts:

‘Come dance with the Great Atlantic Fault

these coal-cutters, these dark hearts,

Relax among rainbows and small town boys –

with us, they shall not starve.’

Voting to end the strike with no agreement. Easington Miners' Welfare Hall, Feb. 1985. Image by Keith Pattison

As Strike winds down to the spectre of closures and ‘the price of coal’, in Barry Hines’ telling phrase, is invested with the heaviness of elegy, one of Sarah Wimbush’s final poems is a profoundly affecting valediction for what will follow the show of hands at Easington Miners’ Welfare of February, 1985. Keith Pattison’s photograph is a grim tableau, softened by the shafts of brilliant daylight that illuminate the raised, supplicant hands of the pitmen. Wimbush’s stunningly prismatic accompanying poem, whose words are a paean to crushed hope, yet finds some salvation in the abyss:

‘When this Welfare Hall

is full with empty spaces

when there is only the stroke

of a muffled drum,

we will bear our white eyes

and grey faces –

the ground rushing to meet us,

windows blown apart by the sun.’ (‘The Black Hole’)

https://www.stairwellbooks.co.uk/product/strike/