search

date/time

| Yorkshire Times A Voice of the Free Press |

Caroline Spalding

Features Correspondent

9:02 AM 5th October 2020

arts

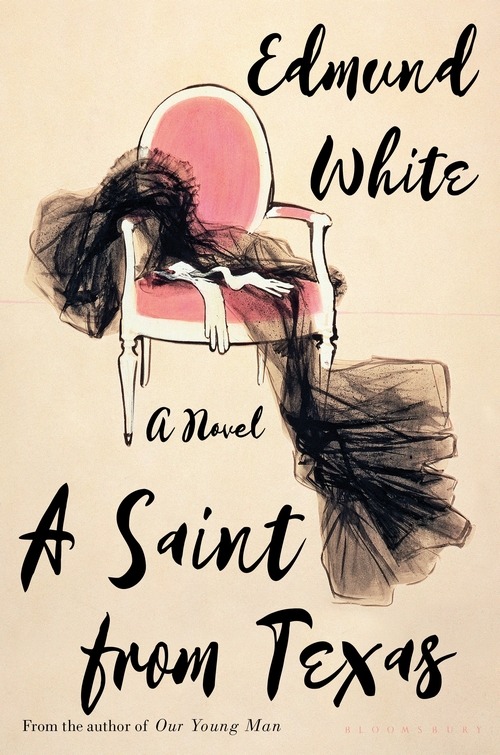

Review: A Saint From Texas By Edmund White

It begins in 1950s Texas, an era we might think familiar but we see the truth and complexity that lies beneath. The customs and general conventions are relayed with unrelenting honesty and candour - there is no pretence, these people are what they are, take it or leave it.

Yvonne, the central protagonist, is a teenager and her prose is written with the nascent naivety of a young woman, infused with the influence of adult hindsight. The stories she tells of her debut, for example, contain youthful wonderment, overlayed with the mature manner of cutting to the chase. Yvonne's father has made his millions in oil, and his new wife is poised to take advantage of this. Yvette, Yvonne's twin, comes across as a bit of an enigma. Although identical in appearance, we are told that in spirit they "were in opposite land(s)".

The everyday life of postwar America is influenced by underlying tensions of race, class, religion, sex and with the feeling that change is afoot. The family have great wealth, Yvonne has great aspirations but around her there appears to be no breadth of thinking. Money is irrelevant, but custom dictates the rules.

These rules transcend the simple-minded nature of the world they inhabit. Yvonne’s world is nuanced, and she is deeply ingrained in it, but she maintains a sense of distance. Beginning her freshman year at the University of Texas she embraces the dream of living amongst French high society. She wants "a castle...(and) a titled husband, not some heavy-drinking cowboy with a mustache and piss-soaked jeans". Through the decades that pass with the novel she remains a blunt Texan beneath the exterior, adept at social disguise (as was de rigueur) and, although faltering at times, she is ruthless in pursuit of what might be around the corner.

Embarking on her life in Paris, Yvonne is desperate to fit in to the new society. She arrives to live with her French tutor’s grandmother, a Madame de Castiglione, affectionately known as Spanky who, whilst she sees straight through Yvonne, deeming her an enfant gaté, gives her a whistle-stop tour of the social conventions which must be followed. Yvonne, as the narrator, helpfully translates most of the French phrases, as if this is a type of diary and she's taking notes and adding her own commentary.

Yvonne enters the society she craves by introductions, a world appearing to the reader so contrived, yet she accepts sans conteste - she wants to learn. Reminiscent of the scene in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar when Ester consumes the finger bowl, believing it to be soup, Yvonne, sometimes clumsily, morphs into a socially acceptable version of herself.

Entirely unfamiliar with French haute société of the 1960s and ‘70s, I would nonetheless wager that what we experience here is exaggerated, even satirized to some extent, and the prose is peppered with Yvonne’s often amusing retorts: “I wondered if he was gay or just French”. Encounters with the less than haute members of société are laughably strained, such as in the forced dinner conversation between Yvonne and the American couple, whom her husband has enjoyed watching having sex in their old Buick.

Edmund White in 2007

The twins, meanwhile, maintain contact through correspondence: Yvette has gone to Columbia on her way to becoming a nun and through these exchanges Yvette comes out of the shadows, revealing more of herself to us through her writing.

There is an unbreakable bond and affinity, despite their dramatic differences. Yvonne receives a letter early on and is "thrilled and troubled... by her way of anticipating every thought of mine, every objection and assent". Yvette’s character manifests many of the dark, underlying themes of the prose, but we slowly develop an affection of sorts for her, if not pity.

As for Yvonne, it's hard to decide whether you like or dislike her, as she too is an enigma. She is coarse, she can be humourous, she can be devilish. She is conflicted, she shows distress, she is ruthless and lives in a world that is driven by status and greed. She swaps her money for title in marriage and from the start she is blunt; there is no love.

Her character darkens as time passes, her commentary increasingly cynical as she resigns herself to her farcical existence. She appears almost constantly adrift, she can be deceived, she becomes bitter. Her extra-marital affairs are in protest; she pays no heed to the potential consequences, but the bitterness forces a new strength of character which can either be seen as an act of defiance or of simply throwing caution to the wind – seeking fulfilment of her own desires.

Also by Caroline Spalding...

Review: Cold Enough For Snow By Jessica AuReview: Good Intentions By Kasim AliReview: Strangers I Know By Claudia Durastanti, Translated By Elizabeth HarrisWalking For Wellbeing – It Really Does WorkReview: The Love Songs Of W.E.B. Du Bois By Honorée Fanonne JeffersThematically, A Saint from Texas is a smörgåsbord, exploring the complexities of being human. There are undoubtedly deep, disturbing undertones and some events, whilst not glossed over, are recounted plainly and without fuss. It is enthralling and unpredictable and perhaps a comment on human fragility. The characters unravel in pursuit of their objectives; they are their own undoing. There are some vile characters in the book, there is some vile behaviour and no justification is offered: this, evidentially, is life.

But recurrent throughout is a strain of dark humour. One scene actually made me laugh out loud - a very rare occurrence - at its absurdity: the reunion of Yvonne’s family, witnessed by the French in-laws, the events so utterly disgusting, but laced with irony, even schadenfreude.

Religion is also a resonant, recurring theme, especially that of sin. How one balances real, human desire with religious allegiance is a tricky problem for Yvette and an engaging sub-plot throughout. The book itself is perhaps a passage of sin, illuminated with themes of greed, lust, deception, envy, pretence, misplaced loyalty; there is barely a single distasteful human characteristic that isn’t embodied by at least one character in the novel.

A Saint from Texas is a complex and highly enjoyable novel – engaging, enthralling, and entertaining. With so much to consider thematically, and a multitude of sub-plots, it is hard to summarise exactly why it deserves attention, and how rewarding a read it proves to be. Not for the faint-hearted, it prompts a myriad of emotional responses; it is intense, provocative and incredibly worthwhile.

A Saint from Texas is published by Bloomsbury.