search

date/time

| Yorkshire Times Weekend Edition |

Caroline Spalding

Features Correspondent

2:41 PM 22nd September 2021

arts

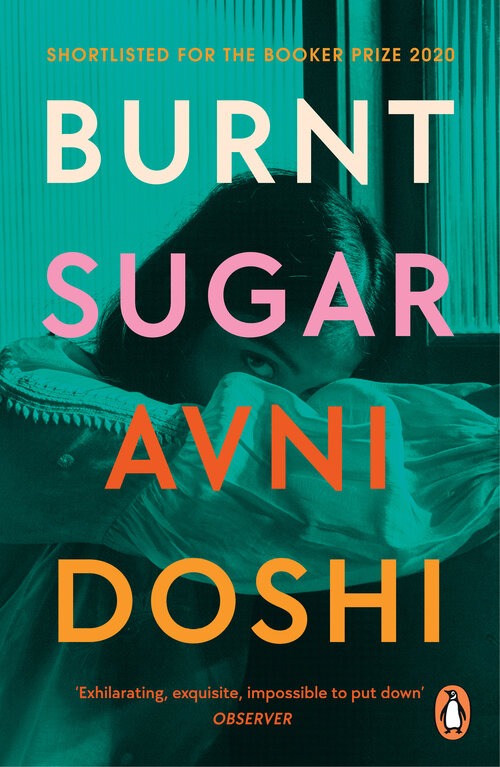

Review: Burnt Sugar By Avni Doshi

The mother, Tara, suffers dementia, declining progressively, and her daughter, Antara, who is the main protagonist, endeavours to understand the condition whilst also reassessing the mother, who she has always held in a form of contempt. Antara tells us her mother gave her her name, which means intimacy, "not because she loved the name but because she hated herself." This gives an insight into the complex connection and history they share; and much of the book tries to comprehend our key motives and drivers, and whether our characters are formed from nature or nurture, or both.

Tara’s dementia is a key theme driving the narrative; connected to this is the role of memory, of what we choose to remember, and what we choose to forget. It makes clear that memories exist not in isolation from our emotions – they can be distorted, both in their forming, and their recollection – but at the mercy of our emotional temperature at any given point.

Antara is an artist: she draws, but with no interest in painting. She tells us: “painting was just an impression. Drawing”, she continues, “I saw, was the grid.” Indeed, she does see the world in lines, rather than colours. Her art, as her vocation, brings both comfort and distress – she observes her surroundings from afar, and to her they comprise little more than line and form, perceived perhaps in monochrome, as if she cannot, or will not let herself become immersed in the full spectrum.

She admits - "I found there was a life in being a spectator instead of a participant," and as a character, she is reluctant at first to let us get too close. But her mother's decline, and her efforts to make her mother recall, prompt her own revisiting of the past. And by dint of the return, we gain a better understanding of what has made her who she is. Her backstory is rich, vivid and often distressing.

Avni Doshi

Antara speaks with candour; she doesn’t hide the painful relationship she has with her mother. The opening line is direct: “I would be lying if I said my mother’s misery has never given me pleasure.” But in her recollection of past events, we can’t help but question its veracity. Antara’s exterior is robust, but she too endures a form of decline. She tells the doctor “I have a suspicion my mother is leaking,” but perhaps unintentionally, she is speaking of her own fear, her own unravelling.

The language is sharp, frank, and, we feel, honest. Antara’s way of communicating has its own distinct nuance: she suggests to the doctor that her mother’s cognitive decline could be linked to intestinal problems. The doctor in response strikes her as if perturbed; she rationalises this as a neurologist preferring to keep their domain apart from the rest of the body, “because a turd can have no relation to the mysteries they seek.”

Above all, this is a story of relationships: mainly between mother and daughter, but beyond, to the broader connection of family, complete with all its flaws and the inevitable challenges. It explores the concept of choice: what we choose, or what is chosen for us. Does Antara feel adrift as a consequence of losing a maternal anchor? Does their relationship complicate her own search for self-identity? Ultimately, the novel reflects the fragility of all we construct, how easily it may all fall apart when our framework starts to falter.

Burnt Sugar can be chilling, and it is certainly poignant. The prose transports us through complex scenarios - we feel we are sharing the stage, observing the awkward glances, inhaling the aromas of the food. Ultimately, I began to feel close to Antara, as if vicariously experiencing her responses.

Also by Caroline Spalding...

Review: Cold Enough For Snow By Jessica AuReview: Good Intentions By Kasim AliReview: Strangers I Know By Claudia Durastanti, Translated By Elizabeth HarrisWalking For Wellbeing – It Really Does WorkReview: The Love Songs Of W.E.B. Du Bois By Honorée Fanonne JeffersI believe the story will strike a chord with all those who have been in Antara’s situation; both those who have a difficult relationship with a parent, and those caring for a loved one experiencing cognitive decline. Even for those who have experienced neither, there is much to which we can relate.

Haunting, bold, unrestrained and beautiful, the novel cuts defiantly into your consciousness, with the ease of a sharp knife lacerating your skin. It won't leave a scar, but instead a lasting memory: and it will leave you wanting more.

Burnt Sugar is published by Penguin Books UK