search

date/time

| Yorkshire Times A Voice of the Free Press |

Paul Spalding-Mulcock

Features Writer

@MulcockPaul

10:08 AM 21st April 2021

arts

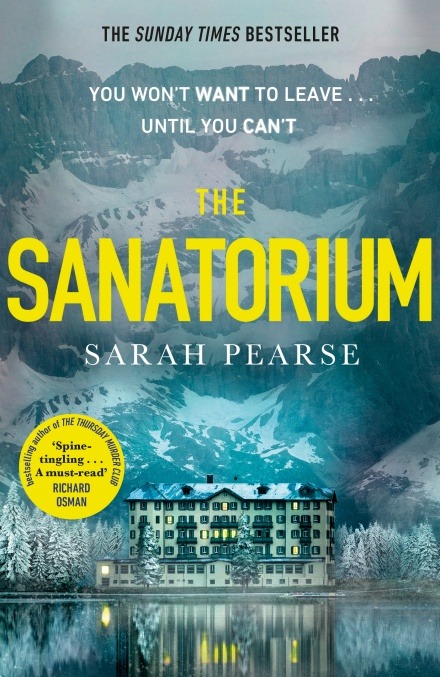

The Traumatic Legacy of Denial: The Sanatorium By Sarah Pearse

Jean-Patrick Manchette said, ‘The crime novel is the great moral literature of our time’. Whilst Pearse has not intended to edify or chasten her reader, she has cleverly anchored her disturbing tale in the morally iniquitous past abuse perpetrated upon some of society’s most vulnerable souls. Unpalatable, disinterred truths form the fetid foundations of the novel’s Gothically-inspired style and substance.

Vaulting this distinctly morbid historical subtext, Pearse, rather like Ross Macdonald, the pseudonym of American Canadian crime fiction writer Kenneth Millar, has also woven psychological tension, sparkling figurative language and ineluctable narrative pace through the gory bones of her beguiling book. The result is a gripping nail-biter which derives its potency and power from the inventive melding of popular genres, eschewing the merely derivative, to become something fresh and compelling.

Whilst I found much to praise in Pearse’s darkly magnetising and jeopardy-laden pages, my own response to the book was nuanced by the conspicuous dichotomy between moments of authorial virtuosity and those less deserving of unalloyed plaudits. For this critically over-sensitive reader, The Sanatorium was less an unmitigated triumph and more a curate’s egg. That said, I suspect my view will see me joining an exclusive club with a membership as miniscule as a government minister’s talent for éclaircissement or lucidity!

Set in the exclusive Swiss resort of modern day Crans-Montana, our chief protagonist Elin, an English police detective with an emotionally bruised and professionally chequered past, finds herself and her patient beau recalcitrant, but fully expensed guests at ‘Le Sommet’. Recently converted from the Sanatorioum du Plumachit into a Bauhaus inspired luxury hotel, Le Sommet is perched eyrie-like high up in the Alps and accessible only by dint of a perilous mountain road winding its way ominously to the faux-sanctuary of its five star, glass-veneered welcome.

Elin’s estranged brother Isaac is celebrating his engagement to his partner Laure, an employee working for the enigmatic brother and sister team, Lucas and Cecile, who manage the avant-garde hotel. Lucas like his gifted architect friend Daniel, is both a hugely successful developer and an infamously unpopular figure of local vilification. The denizens of Crans-Montana would rather the sanatorium be left unmolested and its iniquitous secrets undisturbed.

The engagement is to serve as a holiday for our mentally unmoored protagonist and the belated opportunity to lay the ghosts of her past to rest. There is a febrile, septic dysfunctionality between Elin and Isaac, exacerbated by the recent death of their much-loved mother. We quickly learn that Elin is suffering from a form of post-traumatic stress syndrome, and has been painfully transformed into no more than human flotsam barely bobbing in a fathomless ocean of unrelenting grief and self-doubt. Elin craves resolution and is in search of odious, painful truths known only to her manipulative brother Isaac. The circumstances surrounding the death of her younger brother Sam haunt both remaining siblings, a sodden spectre omnipresent in the minds of both.

Sarah Pearse

Pearse centres her tale on Elin’s psyche as our troubled protagonist battles unseen antagonists in the form of a barbaric and clinically efficient serial-killer, and the shattered mind Elin must rely upon in order to find both the killer and a functional semblance of inner peace. As such Pearse explores duality, the fragility of personal identity, the destructive force of grief and guilt, perfidious betrayal and self-aggrandisement serving to motivate both egotistical megalomania and misogynistic malevolence in its most vile guise.

Vengeance and the repression of both facts and feelings wrap themselves around our dramatis personae, as do the recurrent themes of recrimination, psychosis and personal autonomy. Fittingly, the chief motif of the book is fear…that of both personal extinction and the discovery of sordid truths, as morally unconscionable as they are inescapable.

Our cunningly vulpine author employs a panoply of literary devices to give her compulsive thriller real gusto. Unreliable first-person narration sees us navigating events through the cynosure of a protagonist we cannot trust, because she does not trust herself. We are privy to Elin’s every thought and transported via analepsis to critical moments in the untethering of her mind. Pearse pulls her reader into the frigid heart of the novel by yoking us to Elin’s interior monologue, thereby ramping up vicarious tension and nefarious, deadly intrigue.

Elin’s flawed deductions are far from equivocal statements, her ratiocination blinking on and off like a soon to expire light bulb. This ambience of indeterminacy hovers over an initially efficient plot and serves to haul the reader through events with impressive gravitational force. The pages really do fly by in a blur and our sense of unease is consummately ratcheted up, providing the reader with a white-knuckle ride through the novel’s malevolent mysteries.

Foreshadowing is used with measured aplomb. Dialogue is crisp, its staccato rhythms a drum beat augmented by inexorable vivacissimo. Pearse’s prose is by turns gloriously verdant, if snow dominated, and punchy to the point of breviloquence. However, it is Pearse’s use of place which stands out for particular praise. The hotel itself oozes maleficent menace, its sybaritic allure a façade for its true nature. Depictions of snow are ever-present, chilling the blood coursing through the novels dark heart to freezing point. Snow physically oppressing all it touches, metaphorically echoing the pernicious psychological forces ensnaring Elin’s own mind, ‘ …claustrophobia doesn’t only exist in spaces outside herself, but within her too’.

This claustrophobic ambience is suffused with palpable dread and sustained throughout by dint of our author astutely transcribing the minutiae of every thought manufactured in Elin’s fractured mind. Pearse has the perspicacity of a clinical psychologist and the ability to both understand and convey personality, not in sweeping, asinine statements, but through the careful interpretation of every syllable uttered, and every conscious or unconscious gesticulation made.

The plot, whilst hewn from a clearly intelligent and boldly imaginative mind, did not fully captivate or sustain this reader’s interest. From a flying start red herrings were a tad too obvious for me and consequently shocking plot twists, a desideratum of thriller novels lacked impact, enervated by their predictability. The novel’s dramatic structure is weakened in my view by the premature, if erroneous resolution of the book’s central conflict. A plausible enough revelation melts the ice, holding our interest prisoner. The denouement is not so much flawed as etiolated, and for me serves to justify all that has occurred previously, rather than delivering a surprising knock-out blow.

Character portrayal, though, is superb! We have minor personages who are necessarily static, yet who never descend to become lazy archetypes or plot carriers. The dynamic character is Elin herself, her transmogrification a phoenix like re-birth, albeit accompanied by the scars left behind by slowly healing wounds. Elin is far from likeable, not in that she is unpleasant, but more as a consequence of her inveterate instability and the idée-fixe of understandable, but inimical paranoia. Yet, Pearse makes us care for Elin and urge her on to discovery and salvation.

Also by Paul Spalding-Mulcock...

Word Of The Week : CorpusThe Gallery, Slaithwaite: ‘Ten’ - A Birthday ExhibitionWord Of The Week : SibilantWord Of The Week : PropinquityWord Of The Week : IdiosyncrasySo, a novel I’m extremely glad to have read. Yes, I did find elements of it to be, if not jejune, then perhaps over-egged. However, this is a purely subjective response, the questionable product of quirky fustigation on my part. Dwarfing this idiosyncratic criticism though is a more salient point: Pearse is a truly gifted author and a likely rising star in the literary firmament. An author with her prowess for psychological analysis, descriptive legerdemain and character rendition will doubtless go from strength to strength. Her debut is good, her potential to eclipse it, undeniable!

The Sanatorium is published by Bantam Press

More in this series...

Review: The Stranding By Kate SawyerReview: You Let Me In by Camilla BruceInterview With Victoria PrincewillThe Imposter by Anna Wharton: A ReviewGirl In The Walls By A.J. Gnuse - A ReviewReview: Lightseekers By Femi KayodeAn Interview with Alice Ash - Author of Paradise Block‘ …Really Real Poor People, Surviving Alone Together’: Paradise Block By Alice AshInterview: Neema ShahKololo Hill By Neema Shah: A ReviewInterview With Catherine Menon - Author Of Fragile Monsters‘Ghosts Everywhere I Look. Ghosts Everywhere I Don’t’: Fragile Monsters By Catherine MenonInterview: Bethany CliftLast One At The Party By Bethany Clift: A Review'There Is No Such Thing As Fate, Because There Is Nobody In Control': My Name Is Monster By Katie HaleInterview With Frances Quinn - Author Of The Smallest Man'A Hero Of Our Time!': The Smallest Man By Frances QuinnInterview: Thomas McMullan, Author Of The Last Good ManReview: The Last Good Man By Thomas McMullanInterview With Nikki Smith - Author Of All In Her Head