search

date/time

| Yorkshire Times A Voice of the Free Press |

Steve Whitaker

Literary Editor

@stevewh16944270

9:02 AM 12th May 2018

arts

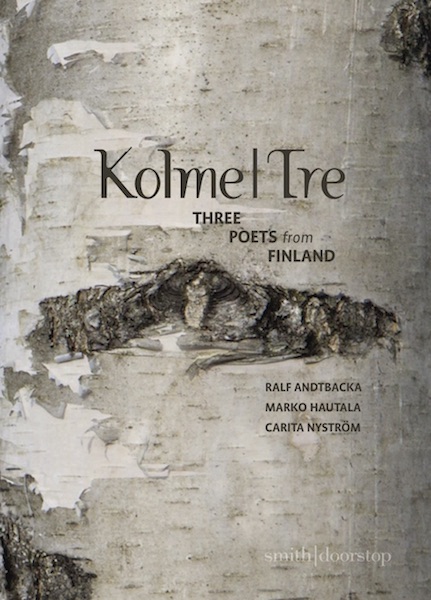

In The Archipelago: Kolme ǀ Tre - Three Poets From Finland. Ralf Andtbacka, Marko Hautala, Carita Nyström

I don't profess to know Finnish poetry, and perhaps being new to the unusual nature of the poetics enables a clearer view. But certainly there is enough of lasting value here to divert, to absorb, and to entertain, in almost equal parts.

The identification of one unifying conceit is unsurprising in a land of endless lakes and forests. An overwhelming, possibly prismatic, sense of 'outside' suggests that Andtbacka, Hautala and Nyström interiorise landscape as infants ingest milk.

Some of the collection's most striking images are directed by, or towards, the sun's strange shadows, the chiaroscuro of light through trees, and the multivalence of water, as though the phenomena gave definition to the observer as much as to the uniqueness of the place observed.

In a brief and intense series of triplets, Carita Nyström's 'The Chaffinch in the Graveyard' liberates the narrator's grieving spirit in one transformative oxymoron: 'On a branch in a sunlit lime-tree / you sing, drunk with life, /over rows of graves.' For Nyström, landscape subliminally recognised lifts mood, often out of darkness. Her power to condense emotion into a brevity of space, to make the moment in the forest, or the sea journey, resound is visionary like Rilke's.

Psychological investment in the natural world is its own reward here. For Ralf Andtbacka, the act of looking deep into water's mirror provokes a synthesis of mind and description where the inherent instability of language-making - 'it slips away, dissolves, transmutes' - may find an ambient resolution. The remarkable simplicity of his 'Light Elegy' is a slow punt down a long river of sparse couplets, whose channels, 'muddy surface', and water-sifted boulders are metaphors for the ebb and flow of emotion, and for 'oxygenating' powers of perception. The poem's final moment is a delicately-realised ameliorant to a suspicion of unease:

or paper-thin insects in August, greenish

against a blue, blue August sky

The looking-glass of landscape is again the catalyst for reflection in 'Tout le monde est triste', whose tristesse is an abstraction, and, bound in the languid sonority of wordflow, commences - 'One drowsy day in August we rowed out on the bay'. Andtbacka's narrator gives an intuitional rendering of archipelagic discontinuity which encourages the strange feeling of mist overhanging the 'resin-dripping conifers' in this 'piece of land separated from land'.

Andtbacka can be very witty. His wanderings over desiccated and dripping urban and rural terrain are ludic; he takes pleasure in easy contrasts. 'Come Over Here and Tell It to My Knife' is a clever, extended oxymoron whose conceit compares the gentle rocking of a baby with that of a knife's rhythmic slicing, 'back and forth: / back and forth.' Elsewhere, the forest's relentless rain is an invocation:

All the forests are drenched

the roads muddy and no longer

passable. The brooks are foaming,

the mere dark and heavy.

(from 'Last Days in the Rainy Kingdom')

Here, an endless visitation of decay is an ironic signifier of continuity, as days and clouds pass by in fleeting moments of celebration.

Ralf Andtbacka's final poem of this collection, 'In the Book Mines', is a meditation on the art of writing, using an extended subterranean metaphor which will inevitably remind the reader of Heaney's justification of his art in 'Digging'. The 'work', here however, is effortful and turgid; the concluding stanza's end-stopped lines are bluntly self-lacerating:

You're a farmhand at the book farm.

You blacken and dung the land.

Sweet Jesus, how you dung the land.

Also by Steve Whitaker...

Poem Of The Week: Off Duty By Katie DonovanBread And Roses: Jennie Lee At Bingley Little TheatrePoem Of The Week: Cargoes By John Masefield (1878-1967)Blown Apart By The Sun: Strike By Sarah WimbushPoem Of The Week: Home Thoughts, From Abroad By Robert Browning (1812-1889)The poet's astonishment at the apparent ridiculousness of the architecture of ancient Egyptian burial in the unequivocally-titled 'Nonsense' is disingenuous. The labyrinthine, ever-deepening system of passageways and vaults that finally lead to nowhere three hundred feet below ground have 'no purpose' beyond the 'nonsense' that they, and the countless thousands of labourers who built them, 'somehow made it all work'.

Similarly, the female 'ceratioid anglerfish', who carries her male 'mates' on her back parasitically until she dies, leaving the male to survive briefly, looks, to Hautala's narrator, like an exercise in evolutionary futility:

A pointless existence in absolute darkness.

In a pressure fifteen thousand times the air pressure.

Yet. Somehow. It has always made sense.

(from 'Sense')

Arriving at simple, persuasive solutions is a common conceit in Hautala's poetry. 'The Birth of Frost' is an engagingly childlike rendering of a five-year-old's exposure to rudimentary physics by a loving father, whilst the hilarious 'The Dog' is a lengthy description of the natural justice of what you get at funerals if you joke on the way to the cemetery. At the graveside, the coffin won't fit squarely in the hole:

"You've got it the wrong way," one of the mourners said.

They turned the coffin. A difficult manoeuvre.

Like a giant insect with no control over its feet.

Hautala's very regular use of full stops adds gravitas to a simplistic poetics. The deeply moving 'Green' describes an arc of detached grief through the visual signifiers of death. Loss is reinforced in a disturbance of colours:

The last time I saw her.

She didn't know where or who.

Several machines with tubes.

Like an experiment.

I was expecting more white.

Fearing its glow in advance.

But the curtains were green.

Like grass.

Waving.

Not knowing.

Where or who.

Ghosts also haunt Carita Nyström's darkness. The poet of opaque vistas, for whom shades of the Gulag tarnish memory - 'In the monastery there was torture' - faces death direct. Loss and grief shape her poems so that the reader is cast adrift in a dully lit, gas-mantled canvas; spectral light infuses words with the mood of Tennyson's Mariana.

A sense of stoicism, resistance to abandonment, conditions Nyström's tone by way of a needful corrective. The poem 'Give Grief Your Time' describes a wise strategy of coping by the facing of pain head on, as the Tragic poets advocated. The fundamentally colourless universe that her narrator endures elsewhere, is mitigated by hope, often manifested in the most commonplace of consolatory tokens:

A strange flower by the roadside

can it be, or just

a bird's feather

landing at your feet

Kolme ǀ Tre - Three Poets from Finland is published by smithǀdoorstop

For more information: www.poetrybusiness.co.uk/shop/973/kolme-tre

.