search

date/time

| Yorkshire Times A Voice of the Free Press |

Steve Whitaker

Literary Editor

@stevewh16944270

3:41 PM 11th June 2018

arts

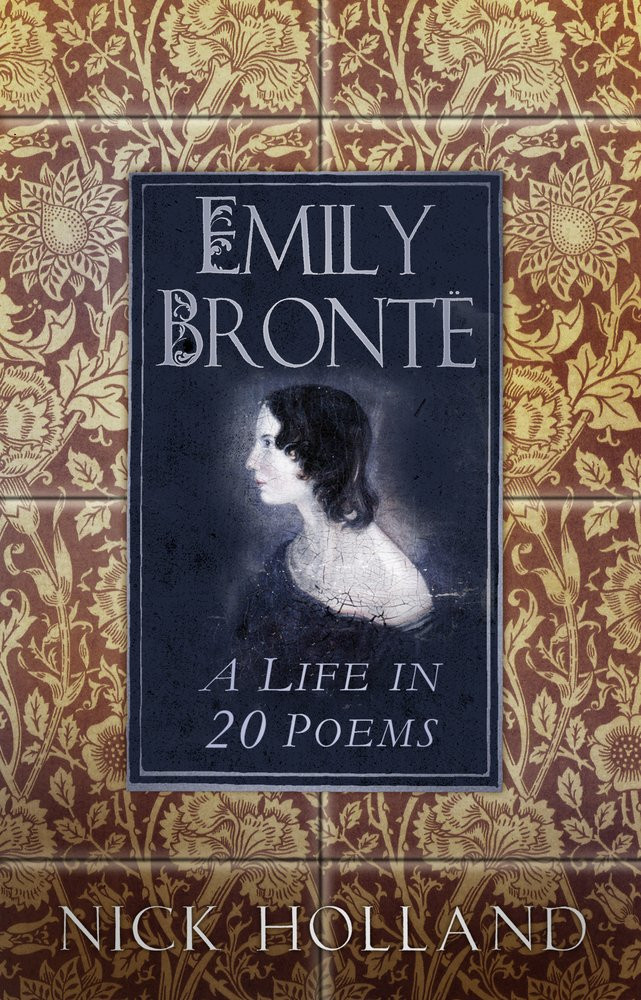

No Coward Soul: Emily Brontë – A Life In 20 Poems By Nick Holland

Holland’s reading of the twenty featured poem finds much existential darkness here, shaped by the austere, sometimes brutal, context of Emily’s life. Her poem of 1841, ‘I See Around Me Tombstones Grey’, is, as he rightly surmises, almost a condition of the poet’s vicarious early suffering. Conceived precisely twenty years after the death of her mother, Maria, the poem, for Holland, is a kind of commemoration, but also of her two siblings, Maria and Elizabeth who died a few years subsequently.

Death was as close to the sensibility of the Brontë sisters as it would have been to many of the malnourished, choleric and consumptive households which lined the steep streets of mid nineteenth century Haworth. At a time when the average lifespan in the town was twenty six, it is no surprise to find a writer infused with a sense of the maudlin, a Tennysonian feel for the colour of elegy.

Holland is quick to find connections here, and he is very persuasive on the impact of the elemental on Emily’s deepest imaginings. If Wuthering Heights is a lengthy elaboration of the intense concision of her poems, then many of those poems find mirrors in the visceral moorland landscape which is as immanent within her as it is a geographical manifestation. Holland finds convincing parallels for her poem of tumult and natural violence, ‘High Waving Heather ‘neath Stormy Blasts Bending’, in real events such as the ‘Crow Hill bog burst’ of September 1824, a cataclysmically violent storm and landslip in which Emily and her sisters were directly caught up. The rhythmically mobile sense of exhilaration felt by Emily’s narrator in the poem must, it seems likely, have been experienced by the children stranded upon ‘the blasted heath’ of twenty years previous:

All down the mountain sides wild forests lending,

One mighty voice to the life-giving wind,

Rivers their banks in their jubilee rending,

Fast through the valleys a reckless course wending

Nick Holland

That Patrick Brontë taught his daughter how to use a pistol illuminates a sense of besieged, unyielding asperity common to both sensibilities at a time of Chartist discontent and fear of the mob. It comes as no surprise to learn that she was a good shot: Emily’s well-documented fearlessness and loyalty to perceived duty leave the reader in no doubt that she would have been prepared to use it.

The pre-eminent instinct here is inward, conservative, and to some degree politically static, and Holland is right to point up the paradox of inner emotional intensity threatening to ‘break the bars’ of propriety. The love Emily felt for her father evidently extended to a near symbiotic relationship with her younger sibling, Anne, with whom she shared everything conspiratorially, like a twin. Providing an anchor of continuity whose unspoken manifestation is interdependency, Anne seems to have enabled the free-flowing efflorescence of her sister’s genius, or at least to have given Emily a critical sounding-board.

Emily’s choice of poetic themes were calculated to burst imaginative ‘fetters’. Holland’s precise inventory of abstract ideas is a glimmering mirror to an emotionally-charged life:

Emily Brontë’s body of poetry as a whole is complex and diverse, and yet there are themes that keep recurring: death and mourning; religion; the mystical power of poetry and creation; the supremacy of nature; and love, often linked to loss.

Also by Steve Whitaker...

Poem Of The Week: Off Duty By Katie DonovanBread And Roses: Jennie Lee At Bingley Little TheatrePoem Of The Week: Cargoes By John Masefield (1878-1967)Blown Apart By The Sun: Strike By Sarah WimbushPoem Of The Week: Home Thoughts, From Abroad By Robert Browning (1812-1889)The austerity of mind which shapes Emily’s poetic instinct is singular and inward-looking. Holland’s acute, and fascinatingly detailed, chapter on the poet’s attitude to religion describes a tendency to Dissent: the subordination of public sacramental observance to a God whose presence is immanent and personal. Emily’s regular foregoing of church services was borne, ironically, out of the same ardency of mind which fired her father’s commitment to Anglicanism; her relationship with God is wrought, instead, in the inner focus of poems such as ‘No Coward Soul is Mine’ whose potency disinters more general truths about life, art and the interiorisation of spirituality.

With an unusually intense power of focus – her muse and raison d’etre are as inwardly indefinable as that yielded by the steady blue flame of a candle in Coleridge’s ‘Frost at Midnight’ - Emily is moved to an absolute loyalty, attachment to home and commitment to duty which are almost preternatural. And Holland rightly imputes a visionary quality to her imagination which is weaned on, rather than prevented by, the domestic humdrum. Her need for the routine of home, and for the narcotic of the moors behind her home, is existential, and is fully revealed in Holland’s vignette of the mind-preoccupied Emily quietly reading whilst kneading dough for the family’s daily bread.

The contrast is starkly represented, and the beautifully drawn, and very moving account of Emily’s demise from tuberculosis at the end of 1848, unaided by any form of medical assistance, is a triumph of phenomenal stoicism against the background ordinariness of the home she could not live without. The half premonitory poems ‘The Old Stoic’ and ‘A Death-Scene’ set the writer’s own tableau. Fully expectant of her own early death even whilst experiencing rude health, the poems are expressions not of foreboding, but of profound acceptance. And they are, as Holland properly infers, powerfully invigorated by her own insight.

The book has weaknesses. A tendency to generalisation and hyperbole is evident: superlatives, unsupported assumptions and non-sequiturs are all characteristic of a tone given to hagiography in places. But these are minor correctives to a fine and handsomely-bound volume whose breadth of research and erudition is staggering. And Holland’s amiable and seductive writing style will not alienate the general reader; entertaining and instructive in equal parts, Emily Brontë – A Life In 20 Poems will make a precisely-judged and accessible addition to Brontë scholarship.

Emily Brontë – A Life in 20 Poems is published by The History Press