search

date/time

| Yorkshire Times A Voice of the Free Press |

Andrew Liddle

Guest Writer

P.ublished 5th January 2026

frontpage

Opinion

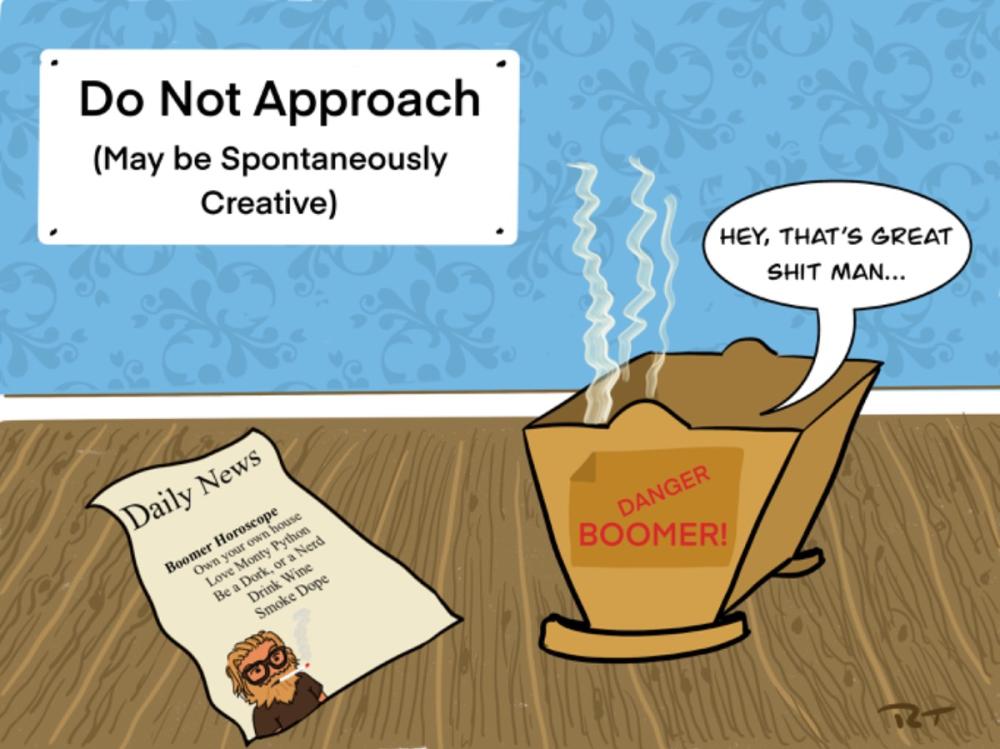

Boom-Boom - Let’s Blow Up The Stereotypes

Andrew Liddle objects to being generationally stereotyped

The phrase “baby boomer” originally described a post-war swell in births, a demographic tide that rose after the Second World War as families postponed by conflict finally took shape. Over time, this fluid historical moment was boxed into a fixed time frame — usually 1946 to 1964 — as if human attitudes could be stacked neatly on a shelf and labelled by decade. The boundaries look tidy on paper, but real lives rarely respect straight lines drawn by social scientists.

Generational labelling works rather like a paint roller: quick, broad and efficient, but incapable of capturing detail. Individual lives — shaped by class, geography, education, temperament and chance — are flattened into a single colour. The result is a portrait that resembles nobody in particular, yet is confidently presented as everyone.

Much of this generational framework originates in the United States and has been imported wholesale into British debate. Along with it has come a habit of caricature. “Boomer” is no longer descriptive; it is accusatory. It now serves as a verbal eye-roll, a way of closing down conversation rather than opening it. The label implies a bundle of assumed flaws — selfishness, technophobia, political reaction — wrapped up and delivered without evidence.

This way of thinking puts the cart before the horse. Instead of asking how economic conditions, historical events or personal circumstances influence people over time, it begins with a label and works backwards, forcing individuals to squeeze themselves into a pre-cut mould. Any contradiction is treated as an anomaly rather than a challenge to the theory itself.

The idea of the post-war “Me Generation” illustrates the problem. Popularised in the 1970s, it suggested a collective turn towards narcissism and self-absorption. Yet the claim that millions of people across different countries and social backgrounds all developed the same personality traits simultaneously is like suggesting an entire forest grew crooked because of one gust of wind. Social change is rarely so simple, or so uniform.

Ironically, generational stereotyping often masquerades as insight while practising prejudice. Younger people are routinely dismissed as fragile, entitled or inattentive; older people are portrayed as greedy gatekeepers, hoarding opportunity and pulling the ladder up behind them. Online spaces, in particular, amplify these crude sketches, where nuance sinks without trace and outrage floats to the surface.

This is not harmless wordplay. Labels laden with contempt have weight. They act like intellectual blinkers, narrowing vision and discouraging engagement. Once a person is reduced to a stereotype, their views can be waved away before they are even heard. The argument is lost, not because it is weak, but because it has been filed under the wrong heading.

Generational myths also rewrite cultural history in bold strokes. The “Swinging Sixties”, for instance, is often remembered as a nationwide carnival of liberation, when in reality it was a patchwork of experiences, unevenly spread and unevenly felt. In many places, daily life carried on much as before. The legend grew louder with time, until it drowned out the quieter, more ordinary realities beneath it.

Economic fortune is another area where generational shorthand misleads. It is undeniable that many who came of age in the latter half of the twentieth century benefited from favourable winds: stable employment, affordable housing, expanding education. But not everyone sailed smoothly. Some encountered headwinds of ill health, redundancy or regional decline. To treat success or struggle as a collective moral trait is to mistake weather patterns for character.

None of this is to deny that shared experiences matter. Growing up before the internet is not the same as growing up with it; living through post-war reconstruction is different from navigating globalisation. But experience is a starting point, not a destiny. People absorb influences selectively, like sponges in the same bucket drawing in different amounts of water.

Ultimately, generational labels promise clarity but deliver distortion. They are blunt tools used where fine instruments are needed. They may offer a sense of belonging or a handy shorthand, but they cannot capture the messy, contradictory reality of human lives.

Every generation eventually discovers that the labels it once wielded will be turned against it. Today’s confident categories will age, crack and crumble, just like those before them. When that happens, perhaps we will remember that people are not products of a single moment in time, but ongoing works in progress.

Blowing up stereotypes may make a mess — but sometimes it is the only way to clear the ground.