search

date/time

| Yorkshire Times Weekend Edition |

Steve Whitaker

Features Writer

@stevewhitaker1.bsky.social

P.ublished 21st April 2022

arts

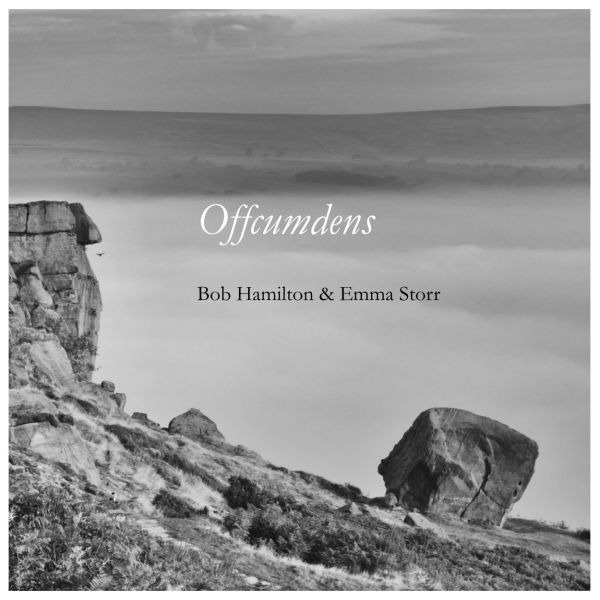

Walking Away: Offcumdens by Bob Hamilton & Emma Storr

Any intertextual inference seems incidental. Offcumdens bears some of the stark moorland reality of Ted Hughes and Fay Godwin’s seminal Remains of Elmet, but the landscapes here are multiform – rural, urban architectural, and idiosyncratically human. And if we can trace some vestige of a connection with Hughes’ aeonic primitivism in Storr’s relationship with the life, and in places, resolute inertia, of the Yorkshire terrain, it is secondary to the poet as observer and celebrant of her ‘expat’ status since 1993. Not least of Hamilton himself, in a skilfully curated poem about the photographer rising to the task of capturing a chiaroscuro sunrise filtered through befogged trees in Ilkley - man, poet and camera in simpatico:

‘His shutter-frame eye

lines up the shot,

a black and white wink

before the morning

sharpens edges,

firs resume their

sentry duty and day

puts on her green coat. (‘Exposure’)

The taking of the shot is a moment of consummation as satisfying as Hughes’ ‘the page is written’ of ‘Thought Fox’, and the sense of completion, of recapitulation, is repeated often in Offcumdens. The clotting of images of wildflowers in the exquisitely sensual ‘Bouquet’, condenses, in sonnet form, the fragrance and emotional allure of a love-letter, as though to garland the inamorata in ribands of Yorkshire’s floral bounty. And in the three simple but resonant tercets of ‘Worship’, a poem of spirituality and transition, of spirituality retained in spite of the crumbling of the material fabric of observance, Storr finds votive comfort in the enduring natural world:

‘We lay offerings

of melancholy thistle.

Birdsong hymns ascend’.

Hamilton’s paired image of a disused Dales barn yields a secular counterpoint which wears the appearance, and the shadow, of a different kind of worship as the clouds roll overhead. Where Church and State meet, as they do in the sonic uplift of a hymn to the Tour de France’s Yorkshire opener, Emma Storr’s instinct for celebration emerges as the former’s power declines into the bicycle-hanging of cultural compromise. But it would be a hard heart that didn’t soften to her cheerful prayer of hope in five formal couplets:

‘Let us raise our sights, our hopes and hearts

as grey clouds disappear above the spire.

Let us glory in the wise and bold

who blessed this church with flying golden wheels’. (‘Tour de France, Blubberhouses’)

Not that Storr’s poetry is lost in terminal exuberance. That sense of completeness which is echoed in the impervious nature of some of the poetic forms she uses, need not exclusively define her purpose: the symmetrical hour-glass of words in ‘Mirror’ delves in and out of the inversion of sky and air in the reflection of the hypnotic accompanying image, to induce a vertiginous sense of ‘diving in clouds’ and ‘walking in sky’, and to create a perspective of contemplation without end.

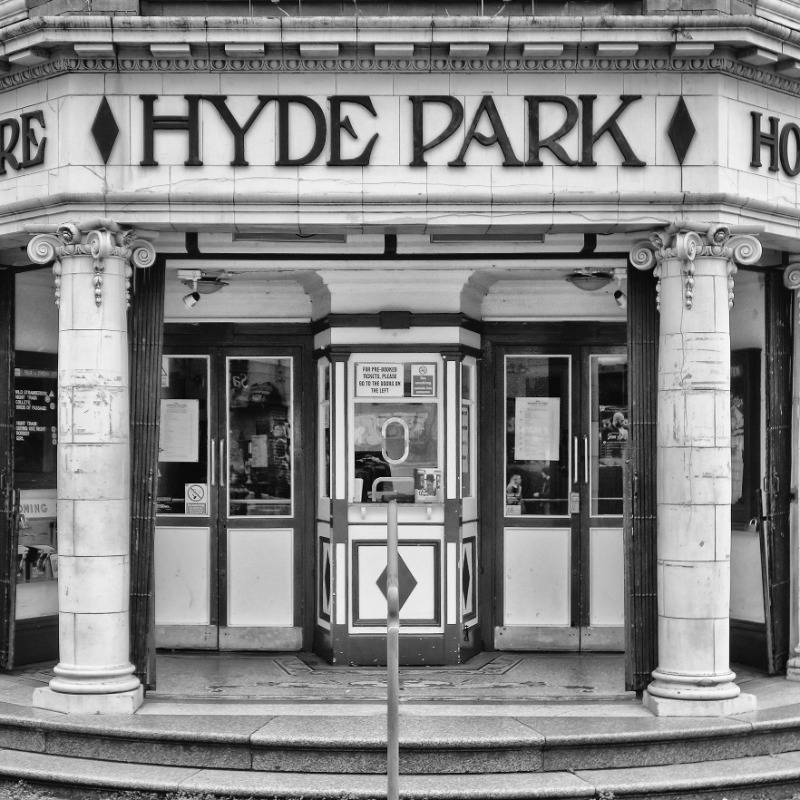

‘Afterwards, we leave without talking.

I think of how we nestled down

into the safe cushioned seats,

while everyday life in Lebanon

walked naked across the screen’.

The intrusion of reality is unsettling here, just as it was for the juvenile Tony Harrison watching the searing monochrome images of Belsen darkening the screen of another Leeds cinema in 1945. Storr seeks liberation for the lost and the forgotten in another poem of visitation: the flat horizons of a post-industrial Hull – viewed through a trellis of rusting stanchions in Hamilton’s persuasive accompanying image – prompt the narrator to reflections on immigration and refugees. Invoking the memory of a philanthropic son of the city, Storr’s wish for a more tolerant, open-armed future is lost, in the end, to the kind of contemplative abandonment that those looking eastwards, like Larkin, see beyond the final isthmus:

‘We watch the Humber swell and rise,

the winter sun retreat behind

The Deep’s prow. Whale song echoes

through the streets on wind-drift waves

from Spurn Point. It’s time to go.

All images by Bob Hamilton

Any barrier between purveyor and purveyed is invisible in the distilled ‘Busker’, whose metronomic rhythms mimic the steady and concentrated attention of the violinist to her task. Subsumed into the emotional uplift of her performance, the busker becomes one with her instrument:

‘The shoppers heard a thread of sound

grow and widen into chords.

They turn and catch a snapshot glance

of beautiful: her poise and skill,

the flow of music out of wood’.

And in one of the finest of Storr’s poems, whose bucolic accompanying photograph of High Royds Hospital as seen over treetops gives the lie to the manias and psychoses of its former occupants, we forget that madness, poverty and destitution once obliged unfortunate sufferers down the same straitened road. ‘West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum’ is a clever, profoundly affecting first-hand account of the disorientation occasioned by institutionalization in hospitals like High Royds and Storthes Hall – where my mother worked for nearly forty years – and of the self-contained terrain in which whole lifetimes were often spent. A picaresque and paranoid parody of a small town, the hospital, its recesses and dark corners, is a place of anxiety where the days melt into years and a sense of home is circumscribed by duration, and the palpable absence of an external world:

‘I think that this is home.

A garden for nesting birds,

the greenest grass,

the smiling face of a clock’.

Offcumdens is published by Fair Acre Press.

Also by Steve Whitaker...

Poem Of The Week: Last Christmas Cracker By Steven MatthewsOur Children's Playless Days: Snagged On Red Thread By Jazmine LinklaterEarth, Fire: Notes On Burials By Jayant KashyapPoem Of The Week: River Mother By Isobel DixonPoem Of The Week: Silk Shirtwaisters From Paris By Janice Warman