search

date/time

Thu, 3:00AM

light rain

5.8°C

12mph

light rain

5.8°C

12mph

| Sunrise | 7:30AM |

| Sunset | 5:06PM |  |

Andrew Liddle

Guest Writer

P.ublished 31st January 2026

frontpage

Spies, Anti-Heroes and the Ancient Journey

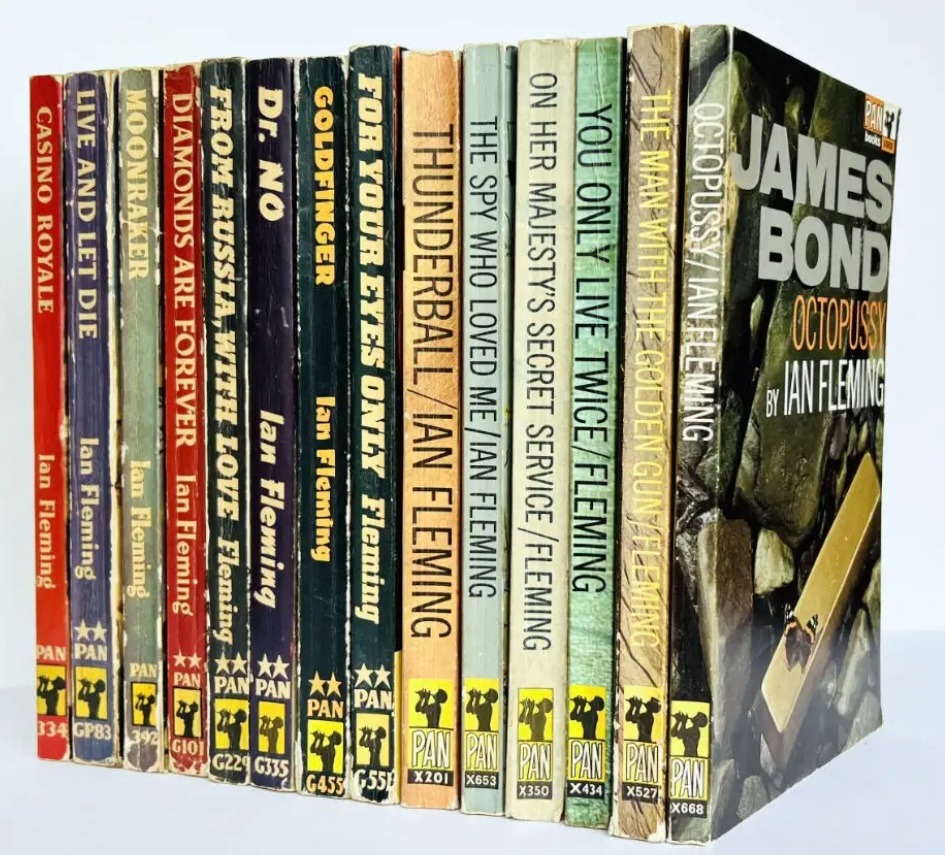

Andrew Liddle considers the spy genre from James Bond to Quiller and the myth beneath the Cold War

Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay

On screen and on the page there were fast cars, shadowy encounters, exotic locations, and beautiful women whose sexuality was far more explicit than anything the upright heroes of earlier adventure fiction might encounter. Compared with the earnest patriotism of John Buchan’s Richard Hannay, or even the morally alert but essentially innocent protagonists of Eric Ambler, these new spies felt dangerous, compromised, and unmistakably modern.

.jpg)

Image by Tumisu from Pixabay

Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) argued that myths across cultures share a common underlying structure - a pattern he famously called the monomyth. The hero receives a call to adventure, crosses a threshold into danger, faces trials, confronts a Shadow, enters an abyss or supreme ordeal, and emerges transformed. Along the way appear recurring archetypal figures: the Mentor, the Ally, the Threshold Guardian. While Campbell’s universalism has often been challenged, his model remains a powerful way of reading popular genres that thrive on variation within familiar structures. Few modern forms reveal this more clearly than spy fiction.

Ian Fleming’s James Bond is the most overtly mythic expression of Campbell’s pattern. Bond’s calls to adventure are clear and irresistible, enacted amid the sadistic card table of Casino Royale, the poisoned glamour of From Russia with Love, the underwater battles of Thunderball, the vaults of Fort Knox in Goldfinger. His Mentors are explicit - M as authority and moral anchor, Q as provider of what Campbell would recognise as supernatural aid - and his Allies range from Felix Leiter to women who assist, betray, or test him. Threshold Guardians are spectacularly physical: henchmen, lasers, fortresses, deathtraps. The Shadow is unmistakable in figures such as Blofeld, Goldfinger, or Le Chiffre, embodiments of greed, nihilism, or ideological threat. Bond repeatedly enters the abyss, survives through skill and luck, and returns scarcely altered, ready to be sent out again. Fleming’s achievement was to fuse ancient archetype with post-war fantasy and consumerist excess, creating a superhero who feels timeless even when his world is extravagantly of its moment.

.jpg)

Image by Oscar fernando Melo Cruz from Pixabay

John le Carré drives the journey inward and darkens it further. In The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, the call to adventure is rarely welcomed. George Smiley does not stride across thresholds but listens, waits, cogitates, reconstructs. The Shadow - most powerfully embodied by the Russian spymaster Karla - is not a monster to be destroyed but a distorted mirror of the hero himself, a doubling that Campbell explicitly identifies as central to mythic confrontation. Mentorship is compromised, Allies unreliable, and Threshold Guardians are secrecy, silence, and institutional inertia. The abyss is ethical: betrayal, sacrifice, and the recognition that one’s own side is morally compromised. Even Smiley’s private life offers no refuge; his wife is serially unfaithful. His transformation is inward and permanent. He survives, but at the cost of isolation and moral exhaustion. Le Carré shows that the hero’s journey can persist even when stripped of glamour, catharsis, or clear moral reward.

Image by Peter Wiberg from Pixabay

.jpg)

In Campbellian terms, Furst radically downplays the visible architecture of the journey while preserving its emotional logic. Mentors exist, but they are shadowy, compromised, and transient figures - resistance organisers, Comintern agents, smugglers - offering partial guidance rather than certainty. Allies are fragile and temporary; love affairs are intense but brief, shadowed by betrayal or disappearance. The Shadow is not a single villain but a pervasive historical force: fascism, secret police, informers, fear itself. There is rarely a single abyss; danger accumulates gradually, decision by decision.

Transformation in Furst’s work is cumulative and melancholic. His heroes do not return victorious or enlightened but wasted by attrition. They learn when to speak, when to disappear, when to betray a cause in order to preserve a person. Survival itself becomes the heroic achievement. In The Polish Officer, the journey unfolds across years of resistance, exile, and loss, with no final catharsis - just endurance and memory. In Night Soldiers, initiation into espionage is not revelation but erosion. In Furst’s world, Campbell’s cycle never quite closes. The hero keeps moving because stopping would mean capture, betrayal, or death.

Taken together, Bond, Palmer, Smiley, Quiller, and Furst’s operatives demonstrate the extraordinary resilience of Campbell’s archetypes. Bond embodies the heroic ideal in its most flamboyant form; Palmer and Quiller show how anti-heroes still pursue the same journey under harsher, more sceptical conditions; Smiley exposes its ethical cost; Furst reveals how it dissolves into endurance alone. The surfaces change, the tone darkens, the victories shrink, but the structure persists.

Looking back to the 1960s, when spy fiction felt dangerous and intoxicating, it becomes clear why these stories resonated so deeply. They spoke to a world of hidden threats, shifting loyalties, and moral uncertainty - yet they did so using patterns as old as myth. Whether in a tuxedo or a raincoat, armed with gadgets or silence, the spy remains a Hero - tested, transformed, and sent back into the shadows once more.